Authors:

Published:

Here is a picture of the Statue of Liberty doing a TikTok dance, as painted by van Gogh, as interpreted by ChatGPT. This is very relevant to my point and we’ll come back to it.

One of the best ways to think about large language models is as universal, personal translators. When I gave a talk at a Spanish-language library conference in Argentina recently, it was an excellent chance to test what LLMs currently offer as translators and what they might become. The answer made me optimistic for how LLMs can work as humanistic knowledge tools, in concert with library values.

This is long, so I’ve broken it up into a few sections that might be helpful to different audiences:

- LLMs are universal translators. This section explains LLM embedding spaces and argues that many of LLM’s most successful applications are essentially translation tasks. I argue that LLMs are “universal translators,” not in the sense that they are perfect but in the sense that they try to translate between any input and any output.

- How I built my own personal translation tools. When I spoke in Argentina, I built my own tools to translate my conference slides to Spanish and to translate other talks to English. This section gets into the weeds of what I did and how I did it. It will be most useful if you are a programmer interested in making more practical use of LLMs, or if you are interested in what might be possible for everyone as LLM tools get easier to use.

- Building my own tools, part 2: real time translation. After my own talk, I watched other talks using a multimodal model to translate slides, and voice recognition and text completion APIs to translate talks.

- What a universal translator means for an innovation lab. The ability to make individual, personalized translation tools changes what all of us should work on next — things that once could have been entire companies are now afternoon projects. This part considers, on the one hand, how my trip made me imagine a bunch of tools I could make and share, and on the other hand whether making and scaling tools still makes sense at all.

- The cooperative principle, AI translators, and human connection. This part reflects on my experience of using technical tools to try to connect with people. I find that they highlight the “cooperative principle” — when two people communicate via an accessibility tool, they have to be more attentive, rather than less, to each other’s social signals, making me optimistic that tools can help to bring us together rather than alienate us.

LLMs are universal translators

LLMs are, in a literal sense, universal translators. They take all of their training data and embed it in a single high dimensional space, an embedding space, and then produce outputs by moving around this embedding space.

The goal of an embedding space is that similar concepts end up near each other, and different concepts end up far away. And the goal of a “large” language model is to embed everything — the space is trained using trillions of tokens representing all of the world’s digital knowledge.

A classic example to understand embedding spaces is this: we take a bunch of data and train an encoder so that if we put in similar words, they encode to a similar location in space. Words like “king” and “queen” each end up encoded as locations somewhere in the embedding space. And then, miraculously, it turns out we can do math on those locations and it makes sense. If you encode “king” into a location, and then subtract the location of “man” and add the location of “woman”, you arrive at the location of “queen.”

This is already a kind of “translation” — we’re literally moving, or translating, from the location of “king” to the location of “queen.” But we can do other kinds of translation with this same technique. We can subtract English and add Spanish, and move from “king” to “rey.” Or we can build encoders that embed pictures and sound as well as text, and encode a picture of King Arthur and come out with the word “king,” or encode the word “king” and come out with an audio file of someone saying “king.”

Embedding spaces translate from everything to everything.

Not surprisingly, a lot of the most promising applications of LLMs can be thought of as translation problems:

- A programmer inputs a comment describing what a function should do in English, and it is translated to an implementation of the function in Python.

- A doctor inputs an image of an x-ray, and it is translated to an English-language diagnosis.

- A user inputs a text description of an image, and it is translated to an image matching the description.

- A lawyer inputs a list of summaries of case holdings and facts provided by a client, and it is translated to a legal brief.

- A social network inputs images uploaded by users, and they are translated to text descriptions for screenreader users.

- And of course literal translation — you click “Translate text” in the Firefox browser and your computer translates it to another language.

This brings us back to the image of the Statue of Liberty doing a TikTok dance, as painted by van Gogh, that opened the article. How did the program “know” what the Statue of Liberty looks like, what dancing looks like, how van Gogh paints, or how those would all go together? It started at a random point in a high-dimensional embedding space, and then translated toward the spot that had the highest overlap of Statue-of-Liberty-ness, dance-ness, and van Gogh-ness, which it could do because it was able to encode and decode both text and images in and out of that space. It could just as easily have navigated to nearby spaces — from Statue of Liberty to Napoleon, or from van Gogh to Monet:

All of the concepts of the world are embedded in the same space and available for translation.

The idea of large language models is that we want the same model to do all of these tasks, because with human problems there’s no way of predicting what’s relevant to what. The lawyer’s brief or the programmer’s code or the Firefox translation could all require a concept map that includes Napoleon or TikTok trends for an accurate translation; large language models are willing to absorb it all and remix in any form.

That’s what I mean by “universal” translator — we don’t have to decide, up front, which facts are necessary for a successful translation, what inputs and outputs to use, because every available idea can be translated in and out of the same embedding space.

Being a universal translator doesn’t make something an accurate translator, or a social benefit. I’m not using “universal” as a superlative or saying it can do any particular translation task well. But a universal translator is a very different tool from a special-purpose translator, and it’s worth experimenting to see what it means to have one.

How I built my own personal translation tools

So, I believe that LLMs are universal translators. And I also believe, as the head of an innovation lab, that getting our hands messy is the best way to improve our intuitions about what’s coming next. So when I was invited to give a talk on disruptive innovation in libraries (adapted transcript) at the Universidad Católica de Argentina for a Spanish audience — a language I don’t speak — it was the perfect chance to experiment with what it means to have a universal translator.

To be clear, I was able to attend this Spanish-language conference not because of the tools described below, but because of the resourcefulness, patience, and enthusiasm of UCA library director Maria Soledad Lago, language professor Mercedes Rego Perlas, and the other speakers and attendees who welcomed me. Many thanks for all of their support, including with these experiments!

The scenario I decided to test was: I’m attending a conference in a foreign language, and I’m going to use low-level APIs to see if it’s possible to build my own tools to solve problems while I’m there.

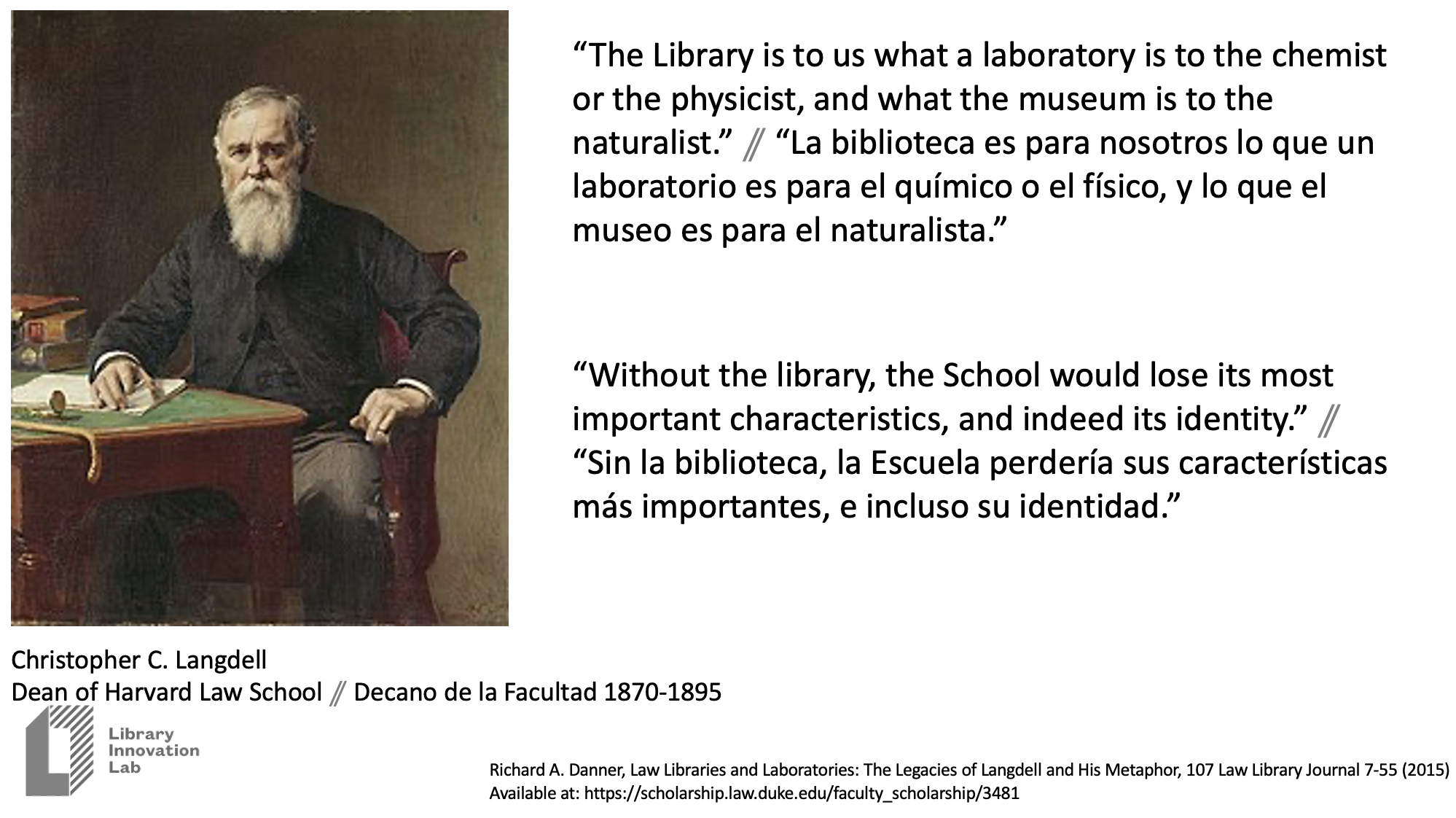

My first goal was to see if it was possible to translate my slides. I knew my talk would be offered with simultaneous translation, but I wanted it to be easier to follow the text on the slides as well. That is, I wanted to show each block of text in the slides in both English and Spanish, like this:

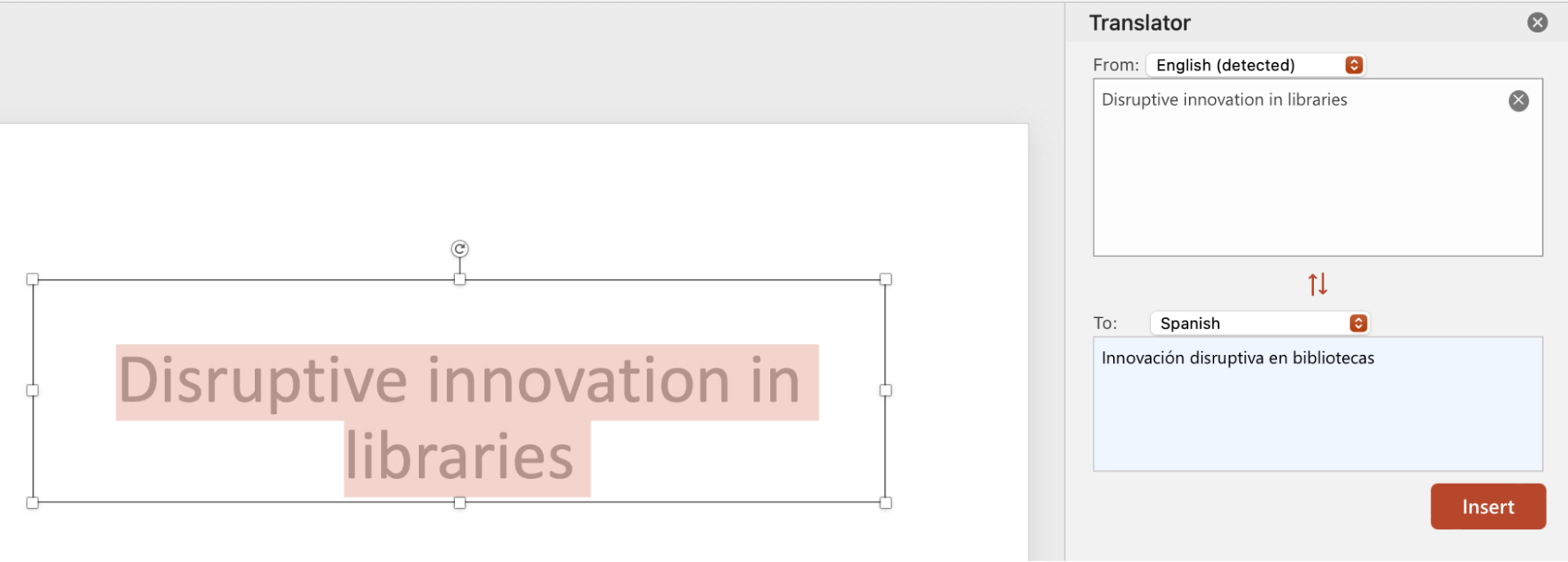

PowerPoint already has a translator built in — you can click a text box and get a translation, like this:

I wanted to see if I could save time by automatically inserting translations for all the text boxes. I also thought I could improve on the PowerPoint feature in a couple of ways:

- I could include round-trip translations in each box, English -> Spanish -> English, which would give me a way to check the translation accuracy without speaking Spanish.

- I could translate entire slides at once, instead of just one text box, which would give the translation program more context to work with.

- I could keep the internal formatting of the text boxes, so the same word would end up highlighted in both versions of the text.

And because the goal was to test whether universal translation can make translation tools more personal and customizable, I wanted to try to do all this in a few hours.

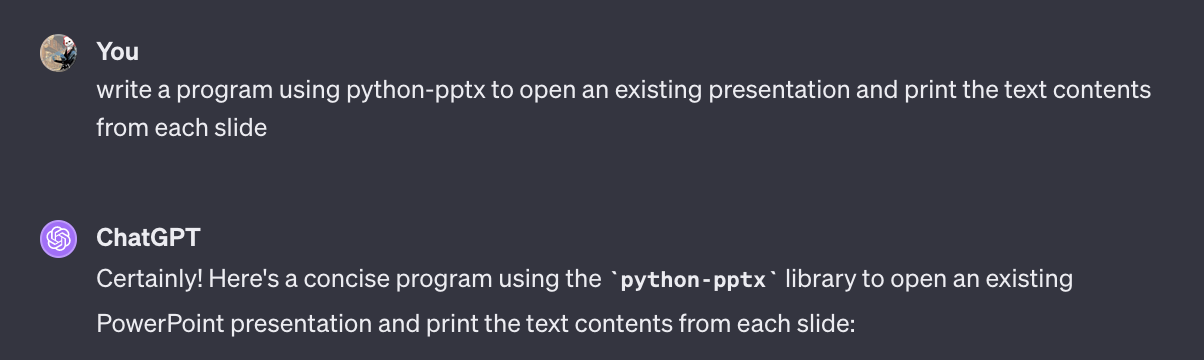

I started by asking ChatGPT to write a program to edit a PowerPoint deck for me:

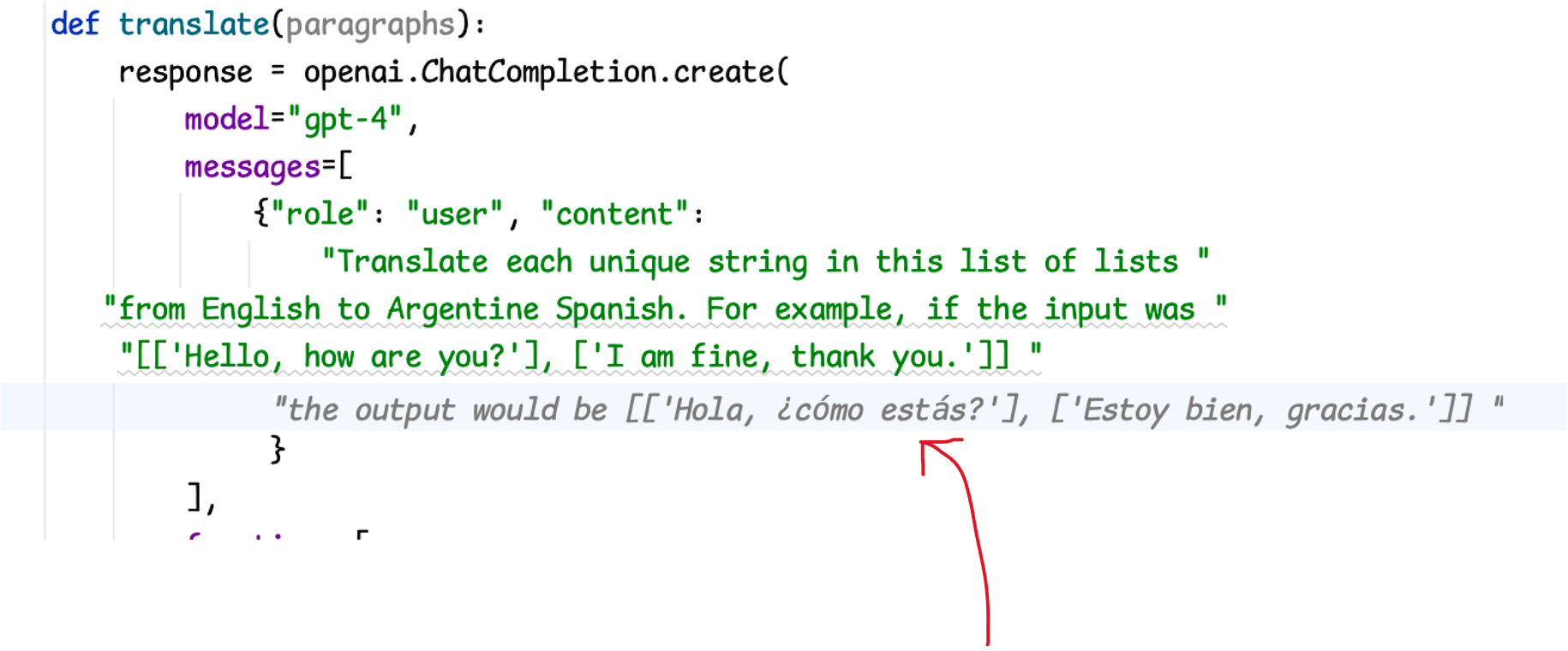

With a little back and forth, I had a starting point — a simple program that capitalizes each word in a PowerPoint. I then started copying and pasting in code to call the OpenAI API. All I’d have to do is take the text blocks for each page, ask GPT4 to translate them to Argentine Spanish, and put the results back in. This gave me a chance to try out OpenAI’s function calling API for structured output, which I had a hunch would help with translation.

I had the fun experience at this point of having Copilot, a GPT-powered coding tool, start to recommend instructions to supply to its sibling in the translation prompt:

Here you can see that I’ve written some code myself to make a “translate” function that takes a string in English and returns Spanish, and I’m writing the instructions that will be sent off to the model. Copilot sees what I’m doing, and suggests the completion of the instruction in gray italic text — including, itself, translating English to Spanish.

The upshot was a script that edited slides to look like this:

This looks like a mess, but it’s just what I wanted! For example, here’s the text of the first block:

“The Library is to us what a laboratory is to the chemist or the physicist, and what the museum is to the naturalist.” -> “La biblioteca es para nosotros lo que el laboratorio es para el químico o el físico, y lo que el museo es para el naturalista.” -> “The library is for us what the laboratory is for the chemist or the physicist, and what the museum is for the naturalist.”

Since the round trip language looks good, I can guess that the Spanish is at least intelligible, and delete the round trip translation and move on.

Checking the round trip translations was a fascinating game, and changed how I think about machine translation. One slide I was suspicious about, for example, translated the English “patron” as “mecenas”:

I wondered if “patrons” came through correctly, or was confusing, so checked what ChatGPT thought, without tipping my hand about the word “mecenas”:

Me: what word is most common for library users in spanish? is there a word like “patrons” that denotes something distinct from commercial customers? ChatGPT: In Spanish, the term “usuarios” is commonly used to refer to library users. “Usuarios” simply means “users.” When specifically referring to library patrons in a context where there’s a need to distinguish them from commercial customers or other types of users, the term “socios” (members) or “afiliados” (affiliates) can be used. However, the context is essential, as “socios” can also mean “partners” in a business sense, and “afiliados” can mean “affiliates” in other contexts. But in general, “usuarios de la biblioteca” (library users) is a standard and clear way to refer to library patrons in Spanish. Me: how would “Los usuarios (socios?) no nos deben su patrocinio.” come across if translated to english? ChatGPT: The sentence “Los usuarios (socios?) no nos deben su patrocinio.” would translate to English as: “The users (members?) do not owe us their patronage.” Here, “usuarios” means “users,” and “socios” can mean “members” or “partners.” The term “patrocinio” typically means “sponsorship,” but in this context, it seems to imply “support” or “patronage.”

I thought it was fun that English-language libraries have this ongoing debate about “patron” as a term, but Spanish libraries don’t seem to have adopted that usage, so I decided to highlight the translation challenge in the slide:

This was one of many probes to check things I wasn’t sure about — you can see the whole transcript here.

All in all, in the space of about four hours, I made a novel tool to translate slides and used it to translate and check the slides for a half hour talk. Throughout, I overtly put a lot of trust in ChatGPT’s language advice, which I knew could be completely inaccurate — an intentional decision to trust the audience of humans to meet me halfway in deciphering any errors ChatGPT might introduce.

Audience feedback was good — influenced, I think, by the fact that I presented it as an experiment and checked in on the translation quality as I presented the trickier slides. Audience members commented that the translated slides were helpful for following a talk in simultaneous translation, and the key points were not lost.

At the same time, it was clear that the translations remained choppy and required readers to work to interpret what I meant. Mercedes Rego Perlas, a linguistics professor at the Universidad de Buenos Aires who worked with me to translate a later version of the talk, commented that the AI was bad at knowing what it didn’t know: if I used untranslatable terms like “loss leader” or “cost center,” the program gamely emitted nonsense, where a human translator would know to ask for clarification and negotiate a compromise, as Mercedes herself did at several points. As always with LLMs, it would take more experimentation to see if a better prompt or control loop could fix that problem — Mercedes was less optimistic than I was.

Building my own tools, part 2: real time translation

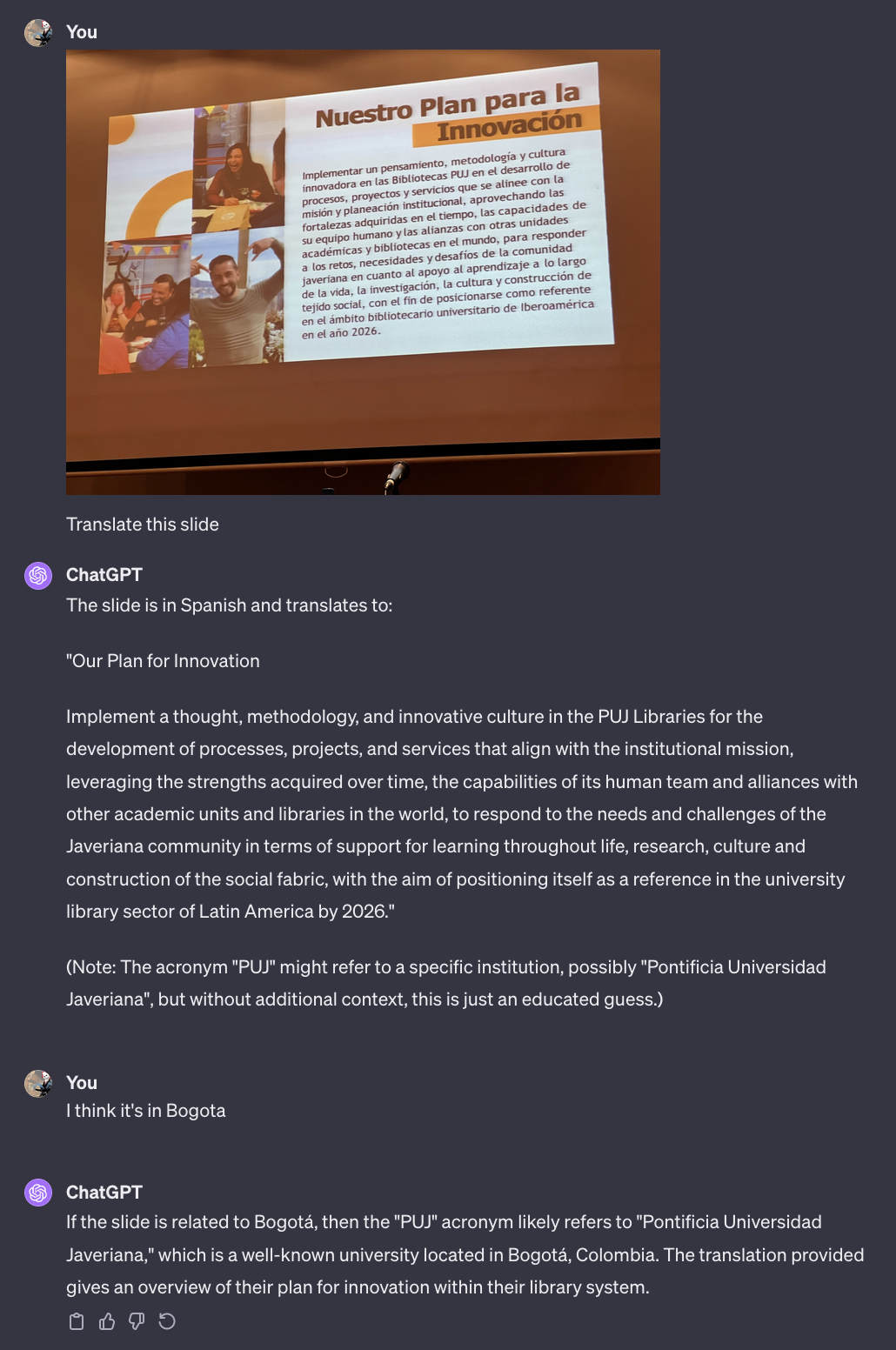

After my own talk, I tested out the “universal translator” in other ways. For example, I tested GPT4’s new vision capabilities by asking it to interpret photos in conversations like this one, from a talk by Andrés Felipe Echavarría, Director de Bibliotecas, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia:

This was a chance to explore how translation works as a matter of culture as well as language — note how the model was able to ask questions and get more context that would let it use outside knowledge to complete the translation.

I also attended an Argentinian digital library conference that didn’t offer simultaneous translation — the 21st Jornada sobre la Biblioteca Digital Universitaria at the Universidad de Buenos Aires. For this conference I decided to test whether it was possible to use low level APIs to build my own simultaneous translator.

I started with some sample code to record and transcribe audio, and adapted it to write audio files and transcriptions to a folder every 10 seconds. I then ran a second program (copying and pasting from the slide translation program) that would translate each 10 second block. And, when those short translations proved choppy, I made a third program that would roll up 100-second blocks of audio to re-transcribe and translate more coherently.

The result looked like this — three separate windows running on my computer that would let me follow what was going on in each talk:

After a few hours I had a prototype that exactly served my needs and allowed me to follow the details of all of the talks I saw.

One of the fun parts of building my own prototype translator was encountering edge cases and mistakes. For example, I was using a speech-to-text model called Whisper that will do its best to transcribe even very quiet staticy noises into text. Users are supposed to filter out silences for themselves, but I chose not to, so during breaks Whisper would translate background noise into hallucinated text — and then, because it uses the previous transcript to predict the next transcript, it would repeat itself in a game of telephone:

You can see how, right at the end, this fades seamlessly into something that would actually be said at a library conference, as it starts transcribing speech and not static and noise becomes signal. Most people would probably not want this in their translation stream, but because I was building my own tools, I could choose to tweak them in this direction.

What a universal translator means for an innovation lab

So, this is amazing! I went to an international conference and tested out a universal translation API that, with the help of my very supportive hosts and human translators, and just a few hours of tool building, changed my experience of the conference. What does that mean for our Library Innovation Lab, which builds open tools to help people collect and preserve and access knowledge?

The tools I built would have each required entire technically sophisticated businesses to invent and maintain a few years ago — and I built them as just a small part of preparing for a single conference. What does that mean?

I’m not the only one asking that question. After OpenAI’s recent DevDay, a number of startups building on OpenAI’s APIs objected that OpenAI’s new tools, like custom agents called “GPTs” or the ability to search and retrieve data from documents, had destroyed their business models. But that wasn’t because OpenAI had stolen anything valuable or done anything very complicated — it was just that, once a universal translator existed, there wasn’t much left to those companies. The things they were doing were easy for anyone to do.

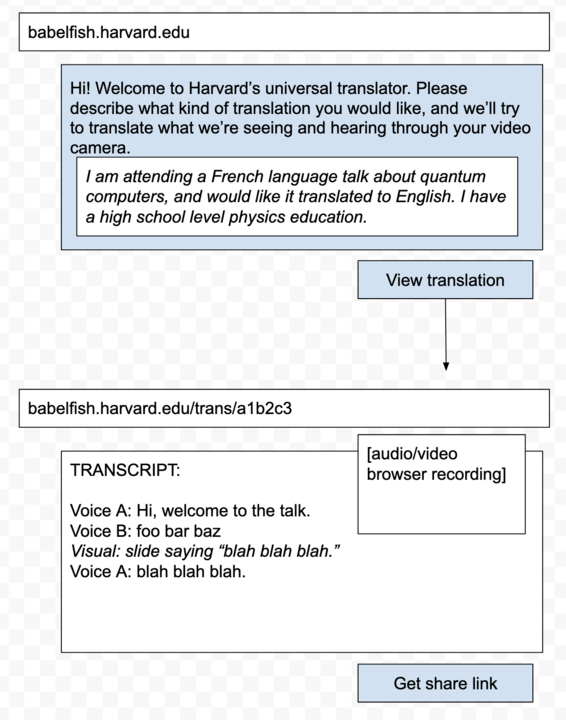

The same thing is happening to us at the Library Innovation Lab. When I got back home, I sketched an idea of what it would look like for Harvard to make an arbitrary x-to-y translation program available to attendees of the many in-person events that take place here every day:

The idea of this sketch is that translation can be from anything to anything: if you’d like to attend a talk, but you need it to be in text instead of visual, and English instead of French, and high school math instead of postgraduate math, you can just describe what you want and the magic of LLM embedding spaces can give you far more access than you had before.

I love this idea, but we didn’t start working on it at the Library Innovation Lab — not because it is too difficult, or unhelpful, but because it is too obvious: soon an app with this shape will exist in multiple versions on every phone, and these features will be built into every existing software product (just as there are already dozens of Zoom apps offering some variation of AI features like this). As an innovation lab, there isn’t anything for us to do … or is there?

Where I think we’ll have a lot to do, as a small team interested in empowering people with knowledge, is to help people navigate the shift from large, standardized tools to small and personal ones. The Silicon Valley software business model has been to make large, standardized platforms, monopolize them and extract value, and as a public interest software lab it’s tempting to follow in the same path and look for interventions that scale — “we want to invent the next Creative Commons!” But the universal translator is so generically useful that our individual relationship to knowledge can change — we can look for interventions that scale in the beautiful way that public libraries scale, where lots of little institutions help every patron solve their own problems. To do that we’ll have to do a lot of work as a lab and community in making sense of what these tools are and how to safely use them.

OpenAI itself, of course, is a classic centralized service with a great deal of power, which makes questions about what happens to it next, what competitors emerge, how they are regulated, and what open source tools are allowed to exist, all very important.

But at the same time, OpenAI is a thinner and weaker control point than the platforms that came before it. Traditionally a service to translate talks has been very different from a service to annotate images or write legal briefs, so each of those services could build deep “moats” around their businesses. By comparison, the scripts to adapt OpenAI’s APIs to each of those tasks are not very long, and the APIs themselves are relatively easily replicated. In many ways OpenAI is important right now not because it has a monopoly, but because it is paying to be first to discover things that then become common knowledge. Our relationship to software platforms has changed.

I see a few ways for libraries to get involved in this shift, and I’m interested in your thoughts on others:

First, we can help our patrons understand the shift and engage with it. A universal translator offers access to timely knowledge that can unlock profound benefits for our patrons. But it’s an access that is still opaque and confusing, in part because it’s more like access to a simulation than like access to a human expert or a database — more like learning to use a weather report or GPS navigation than a book. We can help teach the knowledge literacy skills that make these tools work for people instead of against them, and we can demystify their operation and cut through ways that commercial players try to make things deliberately opaque. Interface experiments like my PowerPoint translation are ventures in making a technology shaped more like its user, and understanding how it can serve human interaction.

Second, we can apply collection development and access skills to the content of the universal translator. LLMs are deeply curated, in hard to see ways: their answers depend on curation of their training data sets, and their extensive manual finetuning workforces, and their hidden system prompts and control loops. They embed — but hide — a great deal of subjective knowledge about the world, and their embedding spaces have strange strengths and weaknesses. We can help to explore those embedding spaces, to signpost them, to fill them out and file off rough edges, just as we do with other knowledge collections. The Library Innovation Lab’s various case studies and projects like COLD Cases, Poems and Secrets, AI Book Bans, and Provenance in the age of Generative AI are experiments in this direction.

The cooperative principle, AI translators, and human connection

But before we buy too far into this view of LLMs as knowledge tools our patrons need access to — is universal translation valuable at all, or just a bad substitute that risks putting people out of work and alienating us from each other? I want to argue that it can be deeply valuable, strengthening the ongoing value and involvement of human beings and human translators.

The cooperative principle observes that there is always translation effort in any conversation, even between two people who use the same language. If I choose to use a complicated phrase like “libraries are turning into cost centers instead of loss leaders” in a presentation — well, first of all, I probably should delete that phrase from the talk, because it’s confusing. But if I keep it in, I know I’ll need to highlight those words, and define what I mean by them, and unpack the connection I’m drawing for my audience, and then make eye contact and check if I need to speed up or slow down. I’ll do work, and my audience will do work, to bridge the gap in meaning. Keeping those terms in the talk will be worth it if the work of translation leads to better understanding.

If we add in automated translation tools to a conversation, how does it change the experience for people doing this work to understand and be understood? I missed a lot on my trip by not speaking Spanish — what did I lose by translating via machine, instead of through a human translator, and instead of through learning and speaking Spanish myself?

Douglas Hofstadter has staked out one end of this argument in the ominously titled Atlantic article Learn a Foreign Language Before It’s Too Late, where he argues that “AI translators may seem wondrous but they also erode a major part of what it is to be human”:

Today’s AI technology allows people of different cultures to communicate instantly and effortlessly with one another. Wow! Isn’t that a centuries-long dream come true, weaving the world ever more tightly together? Isn’t it a wonderful miracle? Isn’t the soon-to-arrive world where everyone can effortlessly speak every language just glorious?

Some readers will certainly say “yes,” but I would say “no.” In fact, I see this looming scenario as a great tragedy. I see it as the beginning of the end of the age-old tradition of learning foreign languages …

The question comes down to why we humans use language at all. Isn’t the purpose of language just the communication of facts? If so, then why not simply go for maximizing the number of facts transferred per second? Well, to me, this sounds like a shockingly utilitarian and pragmatic description of what I view as a perpetually astonishing and quasi-magical phenomenon that lies at the very core of conscious life. …

As my friend David Moser put it, what may soon go down the drain forever, thanks to these new AI technologies, is the precious gift that one can gain only by immersing oneself deeply in another culture and thereby acquiring an entirely new set of ways of looking at the world. It’s a gift that can’t help but turn any human being into a far richer and broader one.

After presenting, watching presentations, and making friends in a language I don’t speak, I am inclined to stake out the opposite end: I think AI translation can accentuate rather than undermine human connection and the subtlety of human language.

When you add in a machine translator, the cooperative work doesn’t vanish, but becomes even more important. Now there are three of you in the room: there’s the large language model, gamely taking inputs like “loss leader” and finding a spot for them in a universal embedding space to try to translate into new outputs, and there’s the humans speaking and listening, gamely looking for familiar facial expressions and words and gestures and clues to meaning, to try to figure out what’s been lost in translation. The two humans have to trust each other and be cooperative partners, because neither of them can follow the process all the way along; they have to be just as attuned and sensitive to nuance as always.

Using machine translation doesn’t feel “effortless,” as Hofstadter suggests; it feels as tricky as any sincere effort at communication. But it also feels like having important new tools to help with that connection.

I don’t think this work that will vanish as LLMs become better translators — it’s work that we are always doing, even when speaking in the same language to someone we know well. And I don’t think it will replace human translators either — there’s a reason married couples might pay a third party human, a marriage counselor, to help translate between them in their own language, and a reason that it often has to be just the right marriage counselor to succeed. But a universal, technical translator will change what we expect from human translators. When we add in a third human as translator, we aren’t looking for them just to play a mechanistic role — we’re involving a third human in relationship with us, who brings their own nuances of meaning to the conversation, and engages in the shared cooperative project of trying to all understand each other.

Not techno optimism, but human optimism

This piece has been somewhat rose-tinted — I had a positive experience with LLMs as translators, and wanted to make a case for why that matters. It matters because knowledge tools always have the power to connect us and make us more human, and we should notice when there are new ways to do that.

I’m telling this rose-tinted story in full awareness of a number of issues that are important and challenging to address — issues with LLM accuracy; the opacity and subjectivity of LLM knowledge curation; the alienation that can come from interjecting technology into social interactions; the economic impacts of automation, of outsourcing, and of data use; the privacy and centralization risks of hosted models and the anti-regulatory risks of open source models. We’ll keep working on those, and using library principles to do it. But I believe, from this experience, that there is something winnable and worth winning at the end of it.

Thoughts? Email me at jcushman@law.harvard.edu.